The more experience you gain, the deeper you can delve.

What did I learn from designing a jeweler’s loupe and its failure?

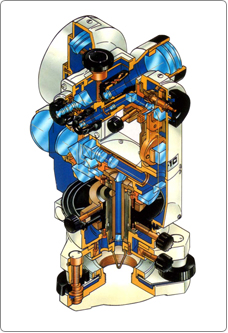

Theodolite cross-section

You have experienced developing many diversified lines of products, haven’t you?

That’s right. The products I was involved in the development of include stereoscopic microscopes, progressive addition lenses, theodolites, and IC and LCD steppers and scanners. The range of categories of products I was involved with is indeed extensive. Having dealt with this variety of products at Nikon, doesn’t it sound a little strange that I have no experience in camera lens design? This is despite the fact that I knew the name of Nikon only as a camera company when I applied to work for them. (Laughter)

Wasn’t it a problem that the products you were assigned to develop varied from one category to another all the time?

That’s true. Because the market I develop a product for today is very different from what I may be dealing with tomorrow. Each market has its own culture. However, overall goals are usually the same, i.e., to achieve certain targeted results by controlling light. Requirements concerning design and precision vary from one category of business to another, and are greatly dependent on how the product will be used in the field.

Product design is highly dependent on product use.

Let me tell you a story about failure. I once was obliged to redesign a product from scratch due to a complaint I received from a client. It was a jeweler’s loupe, the lens of which I designed. The lens used for a jeweler’s loupe is never treated with antireflection coating. This is because the coating hinders the true view of the original colors of jewels. Knowing this, we use material that never deteriorates in quality even when exposed to the air. The light transmission of the material should be optimum. With what I thought was every consideration taken into account, I designed a loupe, and presented it for the client’s testing with confidence. But he was not happy with the result.

What was the problem?

When I watched him test it, he held it close to his eyes and then away from his eyes to view the subject. He simply said, "It looks distorted to me." Of course, I was obliged to totally redesign the loupe. The basic problem was somewhere I hadn’t imagined. I had a preconceived notion that people always held jeweler’s loupes close to their eyes. I designed the loupe with the eye position fixed at a certain distance from the eyes. But in actual use, the distance differs between a loupe and the eye, depending on how each user holds the loupe in front of the subject. I had to redesign the loupe allowing for this kind of unexpected use or situation.

Jeweler’s loupe

It was just a small loupe, but it could have different modes of use from one place or person to another?

Yes. There’s no rule for its use. When you design it, you must take into consideration various situations — use with one eye, viewing with both eyes or use at a lower or higher magnification, etc. With a Nikon reading loupe, the images you see whether from front or rear should look clear. You might imagine that an eyeglass designer determines the curve of an ophthalmic lens surface with no great trouble. As a matter of fact, our designers employ huge amounts of data to create a lens. They take into consideration how the light works when the lens is in use, and how thin and lightweight the lens can be.

So it’s not enough for an optical designer to think only about light?

In essence, the positives or negatives of a lens and optical designs can be evaluated via figures of aberration correction capability. Figures alone, however, are not enough. You have to focus your attentions on exactly how the products will be used, as I explained with the instance of the loupe. You need to pay great attention to materials, manufacturing processes, light sources and image sensors, as well. While you are still a novice, all you can see is just what you are assigned to, or a very limited spectrum of work. As years of experience accumulate, you gain a progressively wider angle of view. For optical design, such a comprehensive perspective is vital.

World-first multi-lens projection optical system.

Mr. Tanaka, you were once a member of a group developing Nikon’s IC and LCD steppers and scanners.

Yes, I was mainly in charge of development of the alignment system. Nikon IC steppers and scanners can superimpose various patterns repeatedly on substrates. Our sensor guides the positioning with the utmost precision. I was in charge of the development of the optical system of this sensor. What’s required here is ultra-precision — precision of less than 1/10th of the line width you intend to print. No compromise is allowed with this.

You also took a key role in the development of the multi-lens projection optical system for use with LCD steppers and scanners.

At that time, there was a strong request among clients to manufacture LCD panels as effectively as possible. They wanted to print a larger size circuit at one time, while also producing as many panels as possible from one glass plate. As plate size gets larger, a projection lens needs to be larger in size as well. But manufacturing a larger lens is extremely difficult and there are technical limitations. These factors led to the creation of our multi-lens projection optical system, which Nikon developed for the first time in the world. I participated in the development of this lens.

I understand your system is designed to cover a larger area of exposure, with an array of many lenses?

Yes. That’s why our system requires no extra-large-size lenses. Even if demand further advances for larger-sized glass plates, we can cope with it by simply increasing the number of lenses in a system.