A self-portrait of Uemura (taken with a self-timer). The shadow of the camera can be seen on his leg.

A self-portrait of Uemura (taken with a self-timer). The shadow of the camera can be seen on his leg.

Photo courtesy of Bungeishunju Ltd.

Naomi Uemura was a renowned Japanese adventurer. In 1984, he was awarded the People's Honor Award* for his numerous accomplishments: he was the first Japanese to climb Mount Everest; he was the first person to climb the highest peaks of five continents; he single-handedly traveled 12,000 km (7,456 miles) through the Arctic by dogsled; and he single-handedly reached the North Pole by dogsled.

This article describes the Nikon F2 Titanium Uemura Special and the Nikon F3 Titanium Uemura Special that Nikon (formerly Nippon Kogaku K.K.) made for Uemura. The cameras were based on the company's F2 and F3 single-lens reflex cameras. (The two custom-built cameras will hereafter be referred to as the "F2 Uemura" and the "F3 Uemura.")

- *This award is bestowed by the Japanese prime minister on those who have distinguished themselves in various fields and are esteemed throughout Japan.

"What is it about Nikon?"

An F2 Uemura on display at the Uemura Museum Tokyo (Itabashi-ku)

In May 1976, Uemura arrived in Kotzebue, Alaska, having just completed a solo 12,000-km expedition across the Arctic by dogsled, and was greeted by a group of press photographers. Almost all the cameras they trained on Uemura were made by Nikon.

Uemura noted that the cameras continued to work in the cold of the Arctic. He asked a Japanese photographer why it was that the press photographers were all using Nikon cameras, adding "When my camera broke one week into the trek, the poor dogs wound up carrying a useless piece of equipment." Uemura was left with few photographs of the expedition because his camera, made by another manufacturer, failed to work in the harsh environment.

The photographer went on to tell Uemura how durable and reliable Nikon cameras are.

"Make me a camera that can survive the North Pole!"

Pushing on ahead to cut through rough ice (shot by Uemura using a self-timer)

Photo courtesy of Bungeishunju Ltd.

In June 1977, Uemura asked Nikon to provide him with a camera for a solo dogsled expedition to the North Pole. He then met with Nikon engineers at the company's Oi Plant to discuss design and quality. The engineers bombarded Uemura with questions—"What is the weather like at the North Pole?", "What is the temperature and humidity?", "How will you use the camera?", "What does dogsledding involve?", and "How much vibration occurs during sledding?"

"The temperature sometimes drops as low as −50°C (−58°F). With the sled clattering along as it cuts through the ice hills, the vibration makes you feel as if you are going up one flight of steps and then careering down another," Uemura explained. The engineers soon realized that the camera would have to be able to withstand both the shock of impact and the lowest of temperatures.

Ways to overcome low temperatures—lubricant and forward film winding

As lubricating oil solidifies at low temperatures, at extremely low temperatures a camera's drive system will seize up entirely. In order to enable the camera to operate at low temperatures, Nikon carried out research into lubricating oil and came up with a special cold-resistant oil that was applied to the drive system of the F2 Uemura. Because this oil is also highly viscous at extremely low temperatures, Nikon used reinforced springs in various parts of the drive system.

With the Nikon F2, the film is wound in reverse so as to flatten it. At extremely low temperatures, however, film tends to harden and then rupture when wound into a spool. Accordingly, with the F2 Uemura, Nikon switched to forward winding so that the film would be subjected to less winding as it was rolled up. To mitigate the loss of film flatness, an extra film anti-curl roller was attached to the camera back.

Since the humidity at the North Pole is very low, friction between the film and the film pressure plate can easily generate static electricity. If a flash of electricity were to occur as a result of this, the film would be exposed. For this reason, an anti-static coating was applied to the film pressure plate.

Comparison of the film winding methods. The image on the left shows the forward winding direction of film in the F2 Uemura, while the image on the right shows the reverse winding of the F2 Photomic. An extra roller has been added to the F2 Uemura. (This particular F2 Photomic also belonged to Uemura.)

The −50°C low-temperature laboratory

An F2 Uemura on display at the Uemura Naomi Memorial Museum (Toyooka, Hyogo Prefecture)

There was a low-temperature laboratory in the basement of the Oi Plant at the time and the F2 Uemura was tested there as well. The low-temperature laboratory was divided into a −25°C (−13°F) laboratory and a −50°C laboratory. Once the test technicians had accustomed themselves to −25°C, they proceeded to conduct tests at −50°C. No matter how many layers of cold-weather clothing they wore, however, the technicians were limited to 15 minutes of testing at a time. It was not a level of cold that they could endure for long, as their eyelashes and eyebrows would freeze solid and their breath would freeze on their spectacles.

All the functions of the camera were checked in the low-temperature laboratory. The shutter speed precision was optimized for approximately −50°C.

Designed to cope with the shock of impact—the first ever titanium camera

To protect the precision mechanisms inside the camera from severe impacts, a robust camera exterior was required. Accordingly, the covers of the top, bottom, pentaprism unit and apron were all made of titanium. Titanium is difficult to work with because it is extremely hard. In order to make its cameras more robust, Nikon had developed an array of techniques for processing titanium. At the time, Nikon was the only company capable of manufacturing titanium camera components. Hence, the F2 Uemura was the first ever single-reflex camera with titanium covers.

A prototype model of the F2 Uemura was placed inside the trunk that Uemura used on his expeditions. The trunk was then rolled down a flight of steps at Nikon's Oi Plant in order to subject the camera to impact testing.

Sealant was also applied to various points on the camera body in order to prevent water from melting snow and ice from penetrating the body of the camera.

"What is that camera?"

Three F2 Uemura cameras were completed in December 1977. In 1978, Uemura used two of the cameras on a solo dogsled expedition to the North Pole and a north-south trek across Greenland. In the space of six months, he shot approximately 180 rolls of film.

On his arrival at the southern tip of Greenland, Uemura was again surrounded by press photographers. "What's that camera?" they asked. The photographers would keep their cameras warm inside camera bags. When one camera stopped working because of the cold, they would switch to another camera fresh from the bag. They couldn't believe that Uemura was able to keep shooting pictures in such extreme cold—without any way of warming his camera.

A camera to meet the challenges of the Antarctic

An F3 Uemura on display at the Uemura Museum Tokyo (Itabashi-ku)

In January 1982, Uemura left Japan to embark on a solo 3,000-km (1,864 miles) dogsled across Antarctica and to climb the Vinson Massif, the continent's highest mountain. Nikon created the F3 Uemura for him to use on this adventure. The F3 Uemura inherited all the cold-resistance and impact-resistance features of the F2 Uemura. It also included refinements that were designed to lighten the load.

Cold-resistant motor drive

Comparison of film advance of the F3 and the F3 Uemura

It is difficult to wind the film advance lever while wearing thick gloves to protect against the cold. There is also the risk of frostbite if gloves are removed or an extremely cold camera is touched with bare hands. The F3 Uemura was thus equipped with an MD-4 motor drive (hereafter, "MD-4"), which enabled the film to be wound on automatically.

The advantage of the MD-4 is its high-speed continuous winding. However, high-speed advance of the film in the low-humidity Antarctic generates static electricity, which can result in flashes of electricity. This cannot be prevented solely by applying an anti-static coating to the film pressure plate. As a result, a time lag was set on the MD-4 in the F3 Uemura so that the film would stop for an instant each time it advanced forward a frame. This mechanism succeeded in preventing charging of the film by allowing static electricity to be discharged while the film was stationary.

More convenient than a self-timer

An F3 Uemura equipped with an ML-1. On the left is a transmitter, while the device on the right equipped with an MD-4 is the receiver. (The ML-1 in the image is not the actual ML-1 used by Uemura.)

"Setting up the tripod, setting the self-timer, pressing the camera's shutter button, running back into position and posing ages. If I am too slow, the shutter is released too soon. If I shoot 10 pictures, no more than a couple come out as intended," said Uemura, who used a self-timer for most of his pictures.

Nikon suggested he use a remote control for self-portraits. With the remote control set ML-1, which was commercially available at the time, the photographer could simply press a button on the transmitter to release the camera's shutter. Uemura liked the idea. "If you press the button over here, the camera automatically releases the shutter over there," he was heard to say.

Lithium batteries that function well at low temperature

The Nikon F3 requires a battery to function. However, it is difficult for ordinary batteries to provide enough power at −50°C. In addition, the motor drive for film advance uses more electricity.

In 1978, Uemura informed the Dry Battery Division of Matsushita Electric Industrial Co., Ltd. (now the Energy Device Business Division of the Panasonic Corporation's Automotive and Industrial Systems Company) that he hoped to use lithium batteries in his radio, headlamps and other devices. Lithium batteries would be less affected by the extremely low temperatures. Matsushita Electric's lithium batteries were chiefly used in industrial-use communication devices and measurement equipment. However, the company decided to work with Uemura and develop a headlamp and battery packs for him. As part of this effort, they developed a lithium battery especially for the MD-4. This battery played a major role in bringing the F3 Uemura to reality.

The headlamp and lithium batteries that were provided for Uemura. The black battery in the middle is the special lithium battery for the MD-4.

Photo courtesy of the Panasonic Corporation

Ending life together

Uemura was due to receive assistance from the Argentine army in undertaking his Antarctica adventure. However, the outbreak of the Falklands War in March 1982 made this impossible. Abandoning his plans, he returned to Japan in March 1983. This also meant that the F3 Uemura would not see action on an actual adventure.

In February 1984, Uemura attempted to become the first person to climb Mount McKinley alone during winter. On February 12, he succeeded in reaching the summit—a stupendous achievement. However, after radio communication between Uemura and a Cessna aircraft on February 13, the adventurer was not heard from again. It is presumed that he had his camera with him in order to record the climb to the summit.

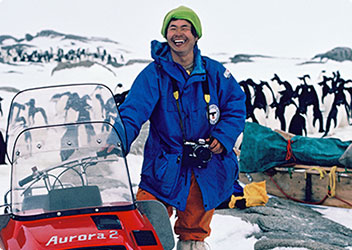

At San Martín Base in Antarctica. Forced to wait a year to leave, Uemura shot 250 rolls of film.

Photo courtesy of Bungeishunju Ltd.

An F2 Uemura and an F3 Uemura are currently on display at the Uemura Museum Tokyo in Itabashi-ku, Tokyo, where the adventurer lived, while an F2 Uemura is also on display at the Uemura Naomi Memorial Museum in Toyooka, Hyogo Prefecture, where he was born and raised. Each of these cameras is in working condition and appears to be awaiting the adventurer's return.

The whereabouts of an F2 Uemura and an F3 Uemura remain unknown. One of these is probably up on Mount McKinley, alongside the body of Uemura.

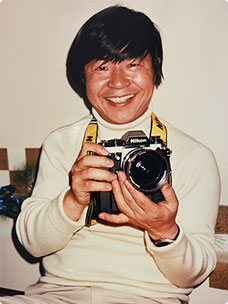

"I only use equipment that I can trust and test myself," said a smiling Uemura holding an F3 Uemura that had just been delivered to his home.

Photo courtesy of the Uemura Museum Tokyo

Display at the Uemura Museum Tokyo in Itabashi-ku

Display at the Uemura Naomi Memorial Museum in Toyooka, Hyogo Prefecture

Compiled with the cooperation of the Uemura Museum Tokyo, the Uemura Naomi Memorial Museum and Panasonic Corporation