A museum is said to be a device that plays back the intentions of its planner. The exhibits in a museum are not simply laid out willy-nilly. Each is displayed in a particular place for a particular reason. Great attention has always been paid to room lighting, so that exhibits look natural. Nowadays, spaces are rendered more impressive by making full use of light.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and the dodo

Alice being presented with her own thimble by the dodo, from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

© Mary Evans Picture Library/PPS

Have you heard of a bird called the dodo? Similar to the goose, this bird makes an appearance in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and in the course of the story suggests that Alice, who is soaking wet from swimming, should dry off by running races. The dodo then presents Alice and her companions with Alice’s own possessions as prizes for the races. This tale has made a deep impression on readers ever since the book was first published, and the dodo has become known worldwide.

The dodo, which also appears in the coat of arms of the Republic of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, is in fact extinct. Found on the island of Mauritius during the Age of Discovery, the rare dodo was hunted to extinction. The only specimen that then remained was a stuffed dodo in one of Oxford University’s museums.

The museum, the first modern one in the world, was opened in 1683. Due to the museum’s poor preservation methods, the sole dodo specimen was disposed of in 1755, except for the head and a foot. The loss of this valuable specimen thus deprived us of the chance to ever again see a dodo in complete form.

Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, was a mathematician at Oxford during the nineteenth century. He likely saw the dodo remains in the university museum and reflected on them. The dodo was to enjoy a splendid revival in his story.

What does “exhibition” mean?

The word “museum” is said to be derived from the Greek word “Μουσείον” (mouseion). A mouseion was a place of learning where scholars and artists dwelt, and where the muses, the goddesses of arts and sciences of Greek mythology, were enshrined.

Although the modern museum started out as a vehicle for the public to view private collections or collections belonging to royalty or the aristocracy, the museum of today resembles the mouseion, in that it also ranks alongside universities as a research institution. Behind most exhibitions is an accumulation of study and investigation carried out to achieve results.

Let us then reconsider the role of the museum. The activities pursued in a museum can broadly be divided into four categories: "Assembly" (the collection and preservation of research materials such as ancient documents and animal fossils), "research and investigation" carried out on these materials, "exhibition"(the display of the materials to the public), and "teaching and dissemination" (making use of these materials and knowledge).

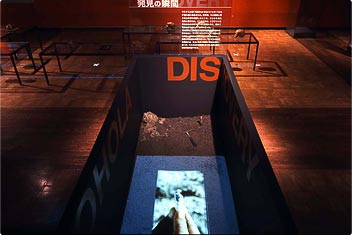

Recreation of an excavation site at which anthropologists scrutinize the surface of the hot desert. (From the accompanying book for Bones of Africa, Bones of the Jomon)

© Forward Stroke Inc.

Exhibiting in a museum is of great significance. With a good exhibition, an emotional connection is established between the exhibits and the viewer, to whom a powerful overall message can be conveyed.

"To exhibit scholarship or exhibit objects?"

It was Fujizo Maeda who questioned the role of the museum in the journal of the anthropology society. In 1904, the School of Anthropology at Tokyo Imperial University (currently the University of Tokyo) staged the Exhibition of Anthropological Specimens, the first ever anthropological exhibition in Japan, and one in which Shogoro Tsuboi had a leading role. It was at this time that Fujizo Maeda answered his own question on the significance of exhibitions—whether it is better to use objects to tell a story or to show objects? Anthropological exhibitions need to use objects to tell a story.

Today’s scholars also have a passion for putting their research locations on display. In 2005, the University of Tokyo’s University Museum staged an exhibition entitled Bones of Africa, Bones of the Jomon. In the words of Professor Gen Suwa, the anthropologist who planned the exhibition (as quoted in the book that accompanied the event), “In this exhibition we wanted to show how research is carried out and how researchers operate.” In this way today’s leading researchers stage scholarly exhibitions that tell a story using objects.

The planner’s setup and the playback

The first requirement in the design of an exhibition is an unmistakable message that lies at the heart of the planning. Based on this message, an environment is created that is designed to elicit eventual understanding on the part of the viewer.

“The museum is a playback device for the narrative that has been set up.”

Visiting Associate Professor Tsuneo Ko, who is in charge of the design of the exhibition at the University of Tokyo’s University Museum, describes the role of the museum as above.

According to Professor Ko, producing an exhibition involves the process of “installation.” The term “installation” here refers to the creation of an artistic space that includes the space surrounding the exhibit and is also used to designate this space, as opposed to simply displaying objects in isolation. The entire space is put to use as a device for communicating the intended message.

The location of the field work for Bones of Africa, Bones of the Jomon was Africa, which is obviously hot. Professor Ko, who was in charge of this exhibition, used red light to represent the research carried out at the university and the anthropological field work carried out on location in Africa. The viewer will probably have noticed this setup—that is, the message that the red light was intended to convey. Here, also, the message is that the planner wants to show the research location.

Museums have in the past investigated methods of natural lighting to make exhibits easy to view. For example, the light from windows was not to be too bright, and the light that entered the building was, ideally, to flow north to south. Between 1% and 7% of the sun’s light was deemed quite sufficient. In the nineteenth century, skylights came to be adopted in almost all museums, following the model of seventeenth-century studios and galleries. Subsequently, however, the creation of spaces using windows and artificial lighting, which had previously been the norm, again came to the fore, so that the sensation of being at the bottom of a well could be avoided.

Red light used to evoke the African location. (From the accompanying book for Bones of Africa, Bones of the Jomon)

© Forward Stroke Inc.

Light that makes for stunning spaces

It is said that light makes for stunning spaces in an exhibition. How should light be used? This is a key factor in the installation process.

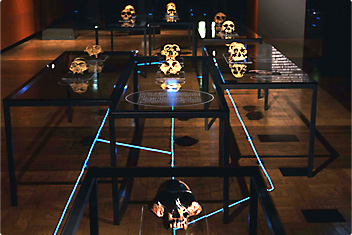

Installation that traces the genealogy of human evolution. (From the accompanying book for Bones of Africa, Bones of the Jomon)

© Forward Stroke Inc.

Here, human bones are being exhibited. The skulls, which point in a certain direction in order to “confront” the visitor, are replicas and can be picked up. In this exhibit they are arranged along lines of light that represent the evolutionary genealogical tree that has led to present day human beings. By walking along the lines of light, the viewer can measure the evolutionary time flow with his or her own footsteps.

The human skull positioned in the center is that of Australopithecus afarensis, the ancestor of human beings. Where did human beings come from and how did they evolve? Anthropologists had long believed that human beings diverged from the closely related chimpanzee 4 million years ago, as no fossils that predate this had ever been discovered.

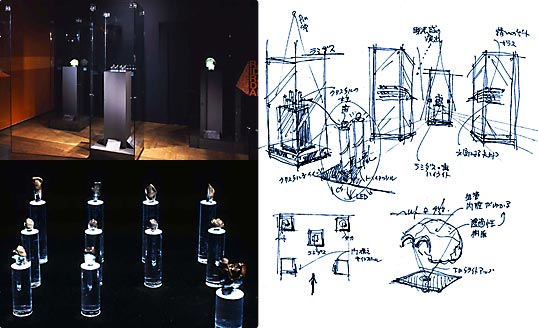

In 1992, however, a research expedition of which Professor Suwa was a member discovered fossils of Ramidus* that date back 4.4 million years. In Ethiopia, this team excavated 17 fragments of tooth, skull and arm bone. The teeth yielded much valuable information, such as age and degree of evolution, and there can be no doubt that, to anthropologists, the tooth fragments discovered are so precious that they can practically be called scientific jewels. The teeth of Ramidus were thus displayed like jewels glittering in the dark.

- *In 2002, Sahelanthropus tchadensis was reported as the oldest set of human fossils, dating back some 6 million to 7 million years.

(Left) The jaw and teeth of Ramidus, the ancestor of human beings, displayed in cases like jewelry. The shining edge display method uses a light that shines up from the base of an acrylic cylinder. (From the accompanying book for Bones of Africa, Bones of the Jomon)

© Forward Stroke Inc.

(Right) Original sketches for “jewel cases”

(From the accompanying book for Bones of Africa, Bones of the Jomon, at the University of Tokyo’s University Museum)

Exhibitions that make good use of light are psychologically effective. If, from afar, you see a space bathed in warm light, you will probably be drawn towards it. This is known as the “light-trap effect.” Spaces that alternate between light and dark evoke alternating feelings of anxiety and reassurance.

(Left) An example of the light-trap effect, as used in “Remembrances in Stone: Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” Images are projected onto the walls by projectors situated at the far end of the walkway. The viewer proceeds, drawn by the far-off light.

© Forward Stroke Inc.

(Right) Original sketch for the “light-trap effect”

(From the accompanying book for Bones of Africa, Bones of the Jomon, at the University of Tokyo’s University Museum)

Professor Ko explains these works as “the practice of museography—making museums more visual.” He discusses what the role of the museum should be and how museums should evolve in step with the changing times. He puts this into practice and then builds on this knowledge. Museums proceeding in this fashion can lead organically to greater understanding and in turn widespread public knowledge. It is precisely through effective exhibiting that museums can resonate with the public.

Editorial contributor / Date of article posted

Visiting Associate Professor Tsuneo Ko, University Museum of the University of Tokyo / June 2009