Beauty resides in harmony with light and shade, as Junichiro Tanizaki (1886-1965) once wrote in his book “In Praise of Shadows.” For decades, bright environments were the norm, and it is only recently that we have recognized how comforting soft lighting can be. In this story, we look at lighting design, and how it can provide us with more natural light that can change throughout the day to create shade and brightness.

The light from fireflies and snow

The phrase “light of fireflies, snow by the window,” the opening lyrics of the Japanese school song “Hotaru no Hikari” (the light of fireflies) originates from the story of two poor students Cheyin and Sunkang, which appears in the Chinese history text “Book of Jin” covering the history of the Jin Dynasty from 265 to 420.

Cheyin caught dozens of fireflies, put them in a silken bag, and studied by the light that they gave off. In winter, Sunkang piled snow around his window and read books by the light reflected from it. Subsequently, the two rose to positions of eminence as government officials, and “achievement by fireflies and snow” became an expression synonymous with the hard-won fruits of painstaking and diligent study.

In Japan as well, light was a precious commodity. During the Edo era, rapeseed oil was worth three times its volume in rice. It was not until the Meiji era (up until which people had burnt rapeseed oil, pine, and bamboo for light) that Japan finally made the leap to widespread use of the oil lamp.

The flickering flame of an oil lamp reflected in a window is beautiful too. This poem by Akiko Yosano (1898-1942) conveys people's desire for a richer lifestyle that will enable them to stay up late and engage in various pastimes.

The author Ichiyo Higuchi (1872-1896), wearing a solemn expression and seated under an oil lamp in front of her sewing equipment. Painted by Kiyokata Kaburaki (1878-1972).

(Housed at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music)

Beyond the glare

However, postwar Japan turned its back on beautiful, pleasing lighting. In the interest of road safety, every nook and cranny was illuminated, and streets and dwellings were lit up. Japan today is the country that appears brightest from space. In the dark of night, the piercing gleam of shop lights feels almost painful in its intensity.

What kind of lighting did people originally find agreeable?

Denmark's Poul Henningsen (1894-1967)—known as the father of modern lighting—was the first person to consider this issue. He is renowned for having designed well over 100 different types of lighting devices. Known as PH lamps, these give off a gentle light and feature innovative designs. Even now the PH lamp still has many fans.

Poul Henningsen—starting when he was 18, he conducted numerous experiments in his quest for harmonious lighting.

The PH Snowball.

Henningsen's most popular creation, the PH5 Plus, which is comprised of four panels. The light cannot be seen directly, no matter which direction the lamp is viewed from.

- (Photographs courtesy of Louis Poulsen)

Henningsen's lamps employ various devices to accord with human sensibilities. First, the brightness is smoothly transformed (or distributed) in order to eliminate glare. The light is softly diffused and then reflected. Creating this kind of pleasing lighting requires just such experimentation and enterprise. It was probably the very fact that Henningsen was from Scandinavia, where there is little sunlight, that led him to produce designs that place such importance on light.

Henningsen realized that indirect lighting, where the light source cannot be seen directly, is pleasant, and that a harsh glare is not.

Glare is the foremost concern in the design of lighting.

In fact, people do not always perceive glare in the same way. The human eye possesses the ability to adjust. As light is received by the eye, the vitamin A in the cells that are used to sense light (the rod cells) is converted into a substance known as rhodopsin, and this enables objects to be seen—even in the dark. In bright locations the opposite occurs. Since the manner in which light is sensed thus changes according to the environment, if an object is extremely bright compared to the surrounding light conditions, the light from it will be perceived as glaring.

Aside from glare, there are many other factors that must be taken into consideration in the design of lighting, such as the irritating featurelessness of homogenous light, the impression of cold created by pure white light, and the possibility that a color balance may be unflattering to the complexion.

Lighting that marks time

In this context, what is the key to creating a pleasant lighting space?

Mr. Kaoru Mende (President of Lighting Planners Associates) has undertaken many architectural lighting design projects, including the Singapore Museum and outstanding buildings in Japan, such as Roppongi Hills, the Tokyo International Forum and Kyoto Station. According to him, “nature is the greatest teacher.”

For example, during the daytime the sun is high in the sky and casts a white light. However, as evening draws near, the sun sinks lower and the light that it gives off turns reddish. This has been our everyday experience of light since the dawn of humanity, tens of thousands of years ago. In Mr. Mende's analysis, lighting that emulates this process is most in accord with people's sensibilities.

In other words, the fact that the elevation and color (or color temperature) of light varies with time is of great significance. For us, lighting designs that mark time constitute pleasant lighting.

In schools, companies, and public spaces, lighting is almost always installed in the ceiling, with whitish lighting being standard. Step inside someone's house, however, and you will find a preference for low positioned, low color temperature, warm lighting, such as low hanging lights over the dining table, or low slung lamps in the living room. The positioning and color temperature of lighting varies according to the degree of tension and relaxation.

Mr. Mende believes that lighting whose aspect changes over time, as day turns to night, is most agreeable and is most in tune with human sensibilities.

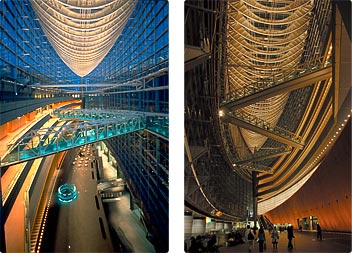

The lighting at the Tokyo International Forum. The keel floats cloud-like in the blue sky. At night it assumes a warmer and more subdued appearance.

Mr. Mende stuck to this conviction when he took on the project of lighting the Tokyo International Forum. Its changing aspect over time, as day turns to evening and then night, is a thing of beauty. In particular, the lighting that illuminates the keel section from which glass is suspended consists of low voltage spotlights directed from outside, so that other sections will not be illuminated by it. As many as 600 lights are used to illuminate the keel section alone.

At the same time, Mr. Mende sets great store by the innate love of the Japanese for a faint light in the darkness. This level of illumination may sometimes strike modern Japanese as gloomy—accustomed as they are to brightness—but it is suitable for a location in which people will meet and chat, though maybe not for people to read by.

Collaboration between the architect and the lighting designer often starts at the planning stage. When the Tokyo International Forum was designed, for example, design of the lighting commenced at the planning stage and was carried out over the course of six and a half years. Recalling this long design period, Mr. Mende comments that “architecture itself is a form of lighting.”

The architect and the lighting designer engaged in intense arguments with one another, each putting his pride on the line as a professional aiming for the very best. They nailed down the concept, drew up the blueprints for the light that strikes the floor surface and the ceiling plane that illuminates it, drew cross-sectional views with people drawn in, and engaged in repeated simulations that enabled them to construct a full-size model. Contour lines were used to show the distribution of light, and numerous detailed calculations were carried out in relation to the brightness distribution, as visible to the human eye. This kind of collaboration between architect and lighting designer results in the best possible lighting design.

Day and night—a beautiful metamorphosis

The appeal of a building made out of glass is highlighted when the lighting and architecture work together as one. Mr. Mende once had a striking experience when he went to see a famous building known as the Glass Church in the suburbs of Los Angeles. Covered in an enormous half mirror, the church reflected the blue sky and seemed like a “cold modern sculpture.”

At dusk the sky turned from orange to marine blue. Reflecting this light, the church also changed in a beautiful manner. What surprised Mr. Mende, however, was that after the sun had set completely, the scene underwent a total transformation. Until just a short while before, the church had been reflecting light, but it was now emanating a gentle light from within. Mr. Mende likens the effect to a “paper covered lantern standing in a vast plain.” He had already left the church and was preparing to go home, but rushed back to it, snapping away repeatedly with his camera.

In the light of this experience, Mr. Mende has since undertaken many lighting designs for glass buildings that employ this phenomenon of transformation between night and day in a captivating fashion.

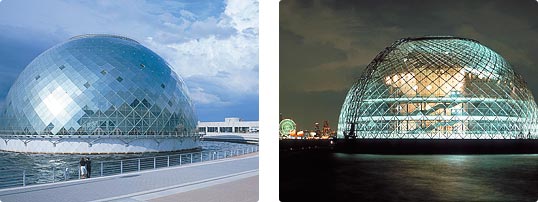

The Osaka Maritime Museum by day (left) and by night (right).

The dome of the Osaka Maritime Museum gives off a metallic reflection in the daytime; however, at night it undergoes a metamorphosis and appears first like a paper covered lantern and then like a jellyfish floating in the sea.

Metal pieces with holes approximately 1 cm in diameter have been inserted in the glass of the dome, and these reflect external light. Although this metal serves to restrict the amount of light entering the dome, the holes account for about 70 percent of the total surface area. In other words, in the daytime the metal serves both to screen out 30 percent of the sunlight pouring onto the dome and to maintain a pleasantly lit environment inside the dome.

At night, however, internal lighting transforms it into a glittering dome, with the structure of the dome and the ships·sails inside it standing out clearly. This dramatic change is magnificent to behold.

The Sendai Mediatheque manifests a playful reversal. This building houses a library, a public gallery and other amenities. It was constructed after a public design competition, in which experts selected the architect.

The Sendai Mediatheque

Left: The light of the sun yields a mirror effect, with other buildings reflected in the Mediatheque's outside walls.

Right: Night witnesses a reversal, with gentle light seeping out from inside.

The daytime-nighttime reversal that Mr. Mende is so taken with is spectacularly manifested using beautiful lighting. The lighting is different on each floor, giving visitors the thrilling impression of entering a different world as they go from one floor to the next.

Sensing and manifesting the passage of time in terms of the transition between day and night, and the use in design of shade as well as light to put people at ease—these are the kinds of sensibility that make people happy, Mr. Mende believes.

Editorial contributor / Date of article posted

Kaoru Mende, President of Lighting Planners Associates / September 2007