Top: Roald Amundsen

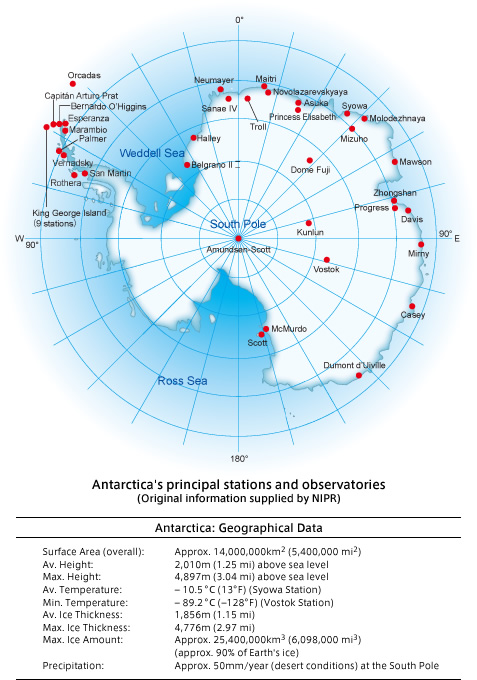

Bottom: The flags of the original 12 Antarctic Treaty signatories

People were not always certain about what was hiding at the Earth’s poles. The Greeks imagined a large continent to counterbalance land in the Northern Hemisphere. They called it Terra Australis Incognita (“the unknown land of the south”).

Now, the consensus is that Antarctica was once part of a “supercontinent” called Gondwana. More than 180 million years ago, tectonic forces began tearing Gondwana apart, sending the landmass that would become Antarctica southward. Vestiges of its once-tropical climate, such as plants and shellfish, remain as fossils to this day.

Charting uncharted territory

In 1520, the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan discovered Tierra del Fuego, at the southern tip of South America. He mistakenly thought it might be part of a new continent.

And in the 1770s, English explorer Captain James Cook crossed the Antarctic Circle and completed the first circumnavigation of Antarctica, but did not prove that a continent existed.

Throughout the 1800s, explorers and hunters from many countries found new islands, landing spots, ocean ice and mountains. Inevitably, there was a scramble to travel inland. On December 14, 1911, the Norwegian Roald Amundsen became the first to reach the geographic South Pole. Meanwhile, different countries began claiming rights to land in Antarctica.

The International Polar Year and the Antarctic Treaty

The idea for an International Polar Year (IPY) came from Lt. Karl Weyprecht, co-commander of the Austro-Hungarian Polar Expedition of 1872-74. He believed coordinated research at the Earth’s poles would answer questions about meteorology and geophysics.

The First IPY (1882-83) included 12 countries, with 13 expeditions to the Arctic and 2 to the Antarctic. The Second IPY (1932-1933) included 40 countries and focused on the global implications of the Jet Stream. The Third IPY (1957-58) coincided with International Geophysical Year (IGY), the idea of physicists who wanted to use technology for scientific research, particularly in the upper atmosphere.

The IGY also gave rise to the Antarctic Treaty. The first arms-control agreement of the Cold War, it has defined international collaboration in Antarctic research since 1961, essentially proclaiming Antarctica an open laboratory for all signatories.

“Neither the Eastern nor Western bloc countries wanted to be involved in conflicts in Antarctica,” explains. Dr. Kentaro Watanabe, head of the International Affairs Section and professor of marine biology at the National Institute of Polar Research. “Scientists and researchers who participated in the IGY had shared life-and-death experiences in remote field locations, and understood the importance of continuing international collaboration.”

The Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition

In January 1957, during the IGY, Japan established Syowa Station, the base of the Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition (JARE), which has sent a research team there every year since its seventh expedition.

Watanabe says JARE’s mission addresses important global issues. “For example, one of JARE’s current main themes of study is global warming.”

Because the continent is so remote from emissions sources, it gives scientists unique sites to monitor the global enrironment. Watanabe says carbon dioxide and pollutants from human activities in the Northern Hemisphere are homogenized as they work their way “down” to the Antarctic in the air and the oceans. The measurements scientists take reflect a global average.

Watanabe also says the relative absence of human activity in Antarctica makes it ideal for studying other subjects. “It provides the best windows through which we can see the history of transformations in the Earth’s ecological systems, geology and geography. We can even study changes in our solar system.”

- 1. Antarctica: From Uncertainty to Fact

- 2. Meteorites and Minerals: Tableaux of History

- 3. The Oceans and the Skies